No products in the cart.

Confined spaces remain some of the most dangerous work environments in the UK, and the numbers prove it. Around fifteen people lose their lives every year, and many of those deaths happen because workers underestimate confined space hazards. Air hazards cause well over half of these incidents, yet you almost never see them coming with your own eyes. That is why hazard-spotting must begin before a foot crosses the opening.

HSE highlights noxious fumes, reduced oxygen, pockets of flammable gas, and risks like flooding or engulfment as the biggest threats. These hazards stay invisible until the moment they cause harm. This guide gives you a practical system to recognise risks early, understand the legal duties under the Confined Spaces Regulations 1997, and decide when a space is simply too dangerous to enter. You learn how to read signs, question assumptions, and treat any enclosed space with caution until evidence proves it safe.

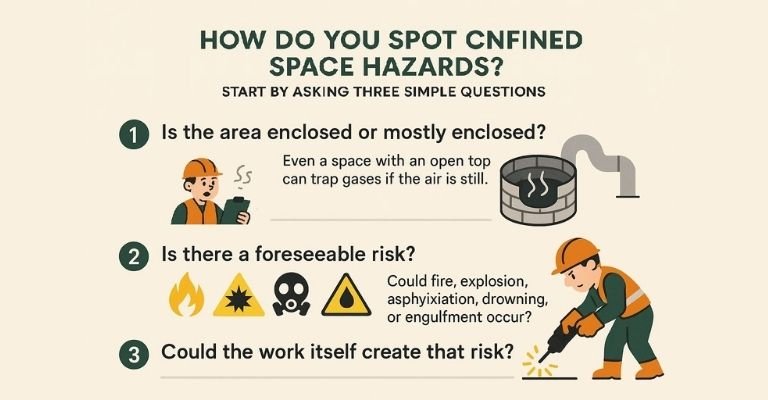

How Do You Spot Confined Space Hazards?

Hazard spotting begins long before you step inside. Many incidents happen because someone thinks the job will “only take a minute.” That single minute becomes deadly when a space hides a risk you didn’t expect. The safest workers take a moment to pause and read the environment. They look at the shape of the space, the purpose of the job, and the history of the area. They ask questions that slow them down just enough to make a safer decision.

A confined space rarely announces its danger. Nothing in the entrance tells you the oxygen level has dropped or shows you toxic gas building near the floor. Nothing warns you that sludge is fermenting and releasing fumes. Spotting hazards becomes easier when you use a mental checklist that guides your attention in the right direction.

Start by asking three simple questions

These questions help you determine whether the space might even be confined under UK law:

1. Is the area enclosed or mostly enclosed?

- Even a space with an open top can trap gases if the air is still.

2. Is there a foreseeable risk?

- Could fire, explosion, asphyxiation, drowning, or engulfment occur?

3. Could the work itself create that risk?

- Activities like welding, cleaning with chemicals, or using fuel-powered tools can create new hazards inside the space.

After asking those questions, look at what the environment tells you. An old tank might contain residue even after cleaning. A trench might fill with water after a rainfall. A manhole might hide gases that migrated from nearby ground.

Hazard spotting is less about what you see and more about what you understand. You treat the space as a story: what entered it, what decayed, what leaked, what settled, and what changed since the last time someone checked.

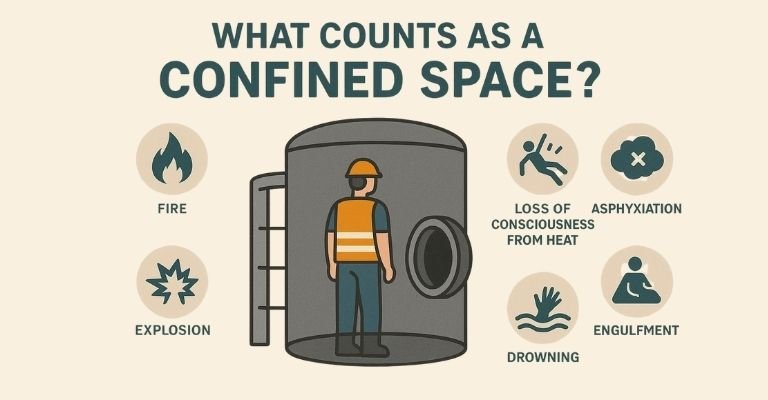

What Counts as a Confined Space?

The UK definition confuses many workers because a confined space is not always small or underground. It is not about size. It is about danger created by the enclosed nature of the space. The Confined Spaces Regulations 1997 define a confined space as any place that is enclosed or largely enclosed and contains a foreseeable specified risk.

This definition stops people from assuming that a space must look cramped or dark to be dangerous. A large open-topped tank can still qualify if gases settle at the bottom. A plant room can meet the definition if ventilation fails and heat builds up. Even a crawl space can count when fumes drift in through cracks and stay trapped.

The law recognises these specified risks

- Fire

- Explosion

- Loss of consciousness from heat

- Asphyxiation due to gases or lack of oxygen

- Drowning

- Engulfment in free-flowing solids

Common examples that clearly count

Tanks, silos, vats, boilers, manholes, sewers, culverts, pits, sumps, ductwork, and underground chambers.

Less obvious examples

Some spaces do not look dangerous until you understand how gases move. A cellar with poor ventilation can be hazardous. A roof void can trap fumes from nearby plant equipment. A trench can fill with carbon dioxide because CO₂ sinks and displaces oxygen.

A confined space is a combination of shape, risk, and conditions. Nothing about the definition says it needs to be small or difficult to enter. It only needs to be enclosed enough for a risk to build unnoticed.

Quick Summary

- A confined space is enclosed or largely enclosed and contains a foreseeable specified risk.

- Examples include tanks, silos, vats, pits, and sewers.

- Less obvious spaces include crawl spaces, plant rooms, and roof voids.

- Temporary confined spaces can form when plastic sheeting or barriers reduce ventilation.

- Size does not matter — risk does.

What Are the Most Common Confined Space Hazards?

Confined space hazards appear in patterns. When incidents are analysed, the same categories appear again and again. Workers face air hazards most often, followed by engulfment, fire, and mechanical threats. Many of these hazards combine inside the same space, which increases danger faster than workers expect.

Air hazards take the lead because you cannot detect oxygen levels or toxic gases without instruments. Many people assume they will smell danger, but most toxic gases do not smell at all. Some of the deadliest gases have no odour, no colour, and no warning before they cause collapse.

Engulfment becomes just as dangerous in certain environments. Grain, powders, and sand move like liquids when disturbed. Workers sink within seconds and lose the ability to breathe long before help reaches them. Fire and explosion risks also increase in enclosed environments. Vapours cannot escape. Heat builds up. One spark becomes enough to ignite fumes or dust clouds.

Common Hazards

- Atmospheric risks: oxygen deficiency, oxygen enrichment, toxic gases, vapours, fumes, and flammable atmospheres.

- Engulfment: grain, powders, sand, slurry, sewage, chemical liquids.

- Fire/explosion: vapours from fuels, solvents, adhesives, resins, dust clouds.

- Mechanical: mixers, augers, agitators, inlets/outlets that activate unexpectedly.

- Thermal/ergonomic: extreme heat, humidity, cramped posture, limited movement.

- Access/egress: narrow openings, vertical ladders, poor lighting, risk of falls.

How Do You Identify Poor Air Quality Risks?

Workers often feel confident when a space looks empty, but air quality rarely matches appearances. Oxygen levels can change gradually as rust forms or organic matter breaks down. Toxic gases can seep through cracks in the ground. Vapours can settle in low areas without any visible sign. You cannot smell low oxygen, taste carbon monoxide, or see hydrogen sulphide until concentrations rise high enough to irritate your senses — and by then it may already be fatal.

Air hazards become predictable when you look at what the space contains or once contained. If the space held waste, sewage, slurry, compost, or organic matter, it can release dangerous gases. If it held solvents, fuel, or chemicals, residues can release fumes long after the tank appears empty. Even clean-looking water can hide biological decay that produces gases.

Good workers learn to read these clues. Air monitoring should never be optional. Testing must happen before entry and continue while the worker remains inside. Gas behaviour changes by the minute, and a safe reading at the start does not guarantee a safe reading later.

Air Quality Clues & Limits

- Spaces that held waste, sewage, grain, or organic matter may release toxic gases.

- Rusting or heavy corrosion can lower oxygen levels.

- Standing water or sludge may release fumes as it breaks down.

- Safe oxygen range: 19.5%–23.5%.

- Flammable gases must stay below 10% LEL before entry.

- Testing must occur before entry and continue during work.

How Do You Spot Fire or Explosion Hazards?

Fire and explosion hazards often hide in plain sight. A confined space does not need to feel warm or smell unusual for an explosive atmosphere to be forming. Vapours can build silently. Dust can hang in the air. A tank that once held fuel or adhesives may still carry enough residue to ignite. Even a single mistake — a spark, a static charge, an unapproved tool — can turn a quiet space into a deadly one.

Many workers assume that a quick visual check will reveal danger. Reality works differently. A tank washed last week may still release flammable vapours today. A sump that looks dry may hide solvent residues inside the walls. Even everyday tasks like cutting, grinding, or welding can generate heat strong enough to ignite vapours that nobody expected to be present.

Ventilation becomes your ally here. A space with poor airflow traps flammable gases near the floor or roof depending on their density. Heavier vapours such as petrol fumes settle low. Lighter gases such as methane rise. Either way, a confined space prevents these gases from escaping. This creates the perfect conditions for an ignition event.

Your job is to spot the signs before work starts. You look at the space’s history, the materials used nearby, and any activity planned inside. You think about the weather, the ventilation, and the equipment you will bring in. When you combine this information, the risks reveal themselves.

- Vapours remain even after cleaning — residues release fumes over time.

- Hot work (welding, cutting, grinding) introduces ignition sources.

- Poor ventilation traps gases at high or low points.

- Everyday tools can create sparks if not ATEX-rated.

- Air testing for flammables must show <10% LEL before entry.

What Physical Hazards Should You Look For?

Physical hazards feel more visible than air hazards, but that does not make them safer. Confined spaces often contain moving parts, mechanical systems, unstable surfaces, or materials that shift without warning. A worker may enter a tank thinking it is empty and safe, only to discover that a mixer blade is still connected to a remote control panel. An auger might restart automatically because a timer activates elsewhere in the facility.

Space restrictions make these hazards worse. In a narrow chamber, turning your body takes effort. Tools catch on edges. Lines snag. Fatigue sets in faster. Even a simple fall becomes dangerous when rescue access is limited. Lighting issues intensify this risk because shadows hide edges, steps, slopes, and gaps.

Engulfment hazards also fall into this category. Grain behaves like a liquid when disturbed. So do powders, pellets, and slurry. Workers often underestimate how fast engulfment happens. A few seconds can trap the legs; a few more can trap the body; after that, breathing becomes impossible. Liquids add drowning risk, especially when the depth is unknown or the surface looks solid but hides a drop beneath.

The safest approach involves understanding the layout, isolating all mechanical risks, and checking everything that could move or collapse. You examine the load above, the walls around you, and the equipment inside. You think about the structure’s stability and any system that could activate without warning.

What Warning Signs Show a Space Is Unsafe?

Warning signs help you recognise immediate danger. These signs might appear before entry or only when you approach the opening. Some hazards feel obvious. Others appear subtle. Workers suffer harm when they ignore these early clues or assume the space “should be fine because nothing happened last time.”

Environmental signs speak loudly when you know how to listen. An unusual smell may come from sewage gases or solvents. Thick air or visible mist might signal chemical reactions, vapours, or humidity that affects oxygen levels. Standing water or sludge can trap gases beneath the surface. Any space that feels unusually warm or cold compared with the surrounding area may indicate a chemical or biological process.

Equipment-related signs matter as well. A gas detector that alarms even once should stop work immediately. A ventilation system that fails to start creates another red flag. A missing permit or incomplete risk assessment signals that the system of work is not ready. Entering without these controls sets everyone at risk.

Human signs deserve the most respect. If anyone near the space begins to feel dizzy, nauseous, confused, or short of breath, the danger is real. Air hazards strike fast and silently. When a worker collapses near or inside a confined space, you must never rush in. Many secondary fatalities happen because rescuers enter impulsively and become victims themselves.

What Checks Should You Make Before Entering?

You never enter a confined space because you feel confident. You enter only when clear checks show the space is controlled and safe. The Confined Spaces Regulations require you to avoid entry whenever possible, and when you cannot avoid it, you must follow a strict system that protects life from start to finish.

Check 1: Do You Really Need to Enter?

This is always the first question. Ask whether the job can be done from outside using a camera, probe, remote tool, or external cleaning method. Many companies remove huge risks simply by refusing entry unless there is no safer option.

Check 2: Has a Proper Risk Assessment Been Completed?

A solid risk assessment identifies every foreseeable hazard, explains the level of risk, and sets out the controls you must use. If the job is high-risk, you also need a permit-to-work. The permit states who can enter, what work is allowed, how long the entry lasts, and which conditions must stay in place throughout.

Check 3: Have All Hazards Been Isolated?

You isolate anything that could move, flow, or activate. This includes valves, pipes, machinery, electrical systems, and rotating parts. You lock, tag, and physically secure everything so nothing can start unexpectedly. Workers then verify these isolations before going near the space.

Check 4: Has the Air Been Tested?

Air testing is essential because most confined space deaths come from invisible air hazards. Testing happens before entry and continues while workers are inside. Monitors must be calibrated and used at different heights to detect oxygen levels, toxic gases, and flammable atmospheres. A single reading is not enough.

Check 5: Is Ventilation Working Properly?

Good ventilation keeps the atmosphere safe. Fans, extraction systems, or natural airflow must run throughout the job to prevent gas pockets forming in corners, low points, or overhead areas. If ventilation weakens or fails, the entry must stop immediately.

Check 6: Is There a Practical Rescue Plan Ready?

A rescue plan cannot be vague or improvised. The rescue team must be trained, equipped, present, and prepared. They need the right rescue equipment, a clear method, and a communication system that works inside and outside the space. A strong plan saves lives when seconds matter.

Check 7: Are All Workers Competent and Properly Equipped?

Only trained workers may enter, supervise, or monitor confined space tasks. Everyone must understand the hazards and the safe system of work. PPE and RPE must suit the risk level and be checked before use. Competence forms the final barrier between workers and harm, so it cannot be rushed or ignored.

Final Thoughts on Spotting Confined Space Hazards

Confined space hazards do not wait for workers to notice them. They build quietly and steadily, hidden by darkness, noise, or still air. A confined space becomes deadly not because it is small, but because its enclosed nature allows risks to grow without warning. The law recognises this danger, which is why the definition focuses on both enclosure and foreseeable specified risks.

Most deaths come from unseen air hazards — oxygen problems, toxic gases, and flammable atmospheres — and global data shows these account for more than half of all confined space fatalities. The UK still records around fifteen deaths each year despite strong regulations. That number proves one thing clearly: hazard-spotting must stay sharp, consistent, and deliberate.

Treat every enclosed space with caution until testing and controls confirm it safe. Do not rely on memory or assumptions. Conditions change. Materials decay. Atmospheres shift. When something feels uncertain, stop and reassess. You give yourself more time, more clarity, and more safety every time you pause.

Confined spaces can be managed safely, but only when workers recognise danger early, test without shortcuts, and follow the safe system of work without exception. The moment you treat the space casually, the risk grows. The moment you treat it with respect, the risk shrinks.

FAQs

1. What are 10 examples of confined spaces?

- Storage tanks, silos, sewers, manholes, boilers, pipelines, utility vaults, ship holds, tunnels, and pits or sumps.

2. What are the 4 gases in a confined space?

- Typically monitored gases are oxygen, flammable gases or vapours (like methane), carbon monoxide, and hydrogen sulphide.

3. What is a high risk confined space?

- A high-risk confined space is one where serious injury or death is likely from hazards such as toxic or flammable atmosphere, engulfment, flooding, or rapidly changing conditions.

4. What is confined space in simple words?

- A confined space is a small or enclosed area that you can get into, but it has limited ways in or out and isn’t meant for people to stay in long-term.

5. What are the four types of confined space hazards?

- Main confined space hazards are atmospheric (toxic, low oxygen, explosive), engulfment (solids, liquids), configuration or entrapment, and other physical hazards like energy, noise, heat, or moving machinery.

6. Why 24V in confined space?

- 24-volt equipment is used in confined spaces to reduce electric-shock risk and limit sparks that could ignite flammable gases, while still providing adequate lighting or power for tools.

7. What are the three conditions for a confined space?

- A confined space must be large enough to enter, have limited or restricted openings for entry or exit, and not be designed for continuous worker occupancy.

8. Is it safe to touch 24V?

- Touching 24V is usually considered low risk, but it can still be dangerous in wet, cramped, or metal environments; always follow electrical-safety rules and site procedures.

9. Which bulb is used in confined space?

- Confined spaces typically use low-voltage, explosion-proof or intrinsically safe LED work lights specifically rated for hazardous locations.